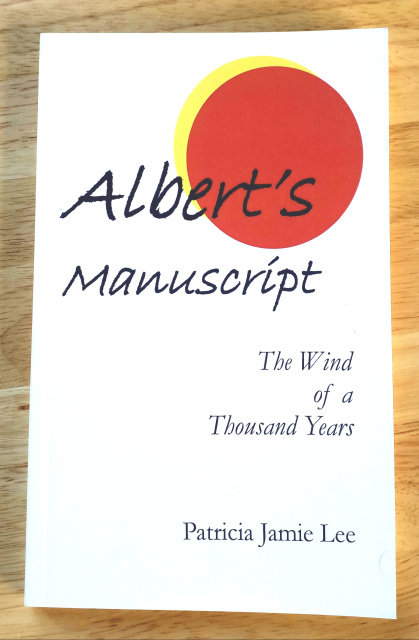

- Albert's Manuscript

Albert's Manuscript

SKU:

$12.95

$12.95

Unavailable

per item

This powerful tale hit me like a storm. I wrote for 6 days straight and when it was over, the book was done. I've often thought that it was not written by me but given to me by a higher source. Later, this story became the basis of my little Bead People project. I do hope you will hear what Albert has to say to us--give it a read and then carry it in your heart.

The price includes USPO book rate shipping. If you want to get your book sooner, it is also at Amazon.

Paperback, 87 pages

Many Kites Press / ISBN # 9781937238018

|

Prologue and Excerpt of Albert's Manuscript by Patricia Jamie Lee

Albert's Manuscript Dear Reader, For many years I was working on a novel series in which the characters continually seek the intersection between heaven and earth. In one of the novels a character named Albert showed up, an old man by then, with a mysterious manuscript that told of his journey to the spirit world as a young Lakota man. Albert’s Manuscript was woven into the main novel, but I had no idea of its contents. One winter day in 2004 I felt stuck in my writing and decided to see what the manuscript actually said. I bought a cheap spiral bound notebook and started writing. Albert’s manuscript emerged over six days in quick nonstop writing sessions. I was simply carried into his story. I put no pressure on the words to perform, asked nothing of them, and allowed Albert to say whatever he wanted to say. When it was done, it was done. Nothing more could be added. Albert is not a real person, not in this realm anyway. You will not find him here, but I suspect he is not very far away—and had something he wanted to say. I was willing to listen and write. Since that time, I created a short version of The Wind of a Thousand Year, illustrated it myself, and sent it out into the world with my little Bead People. Since that time, over seven thousand copies of the little Wind book have gone to over 40 countries carrying their message of peace. Do check out The Bead People International Peace Project to read the story and get involved. The website is www.thebeadpeople.com. Also, visit me at my blog, No Ordinary Life and join our community of peacemakers by subscribing at www.jamieleeonline.com. We certainly could use a little more peace in the world. As for me, I’m loving my new life in northern Minnesota in our little hand-built straw bale house with our gardens expanding around us. Tell me about your life. And now, here is Albert’s story. Patricia Jamie Lee When I was a young boy, I used to look at my grandfather and see his bones beneath his thin skin and wonder how he crawled out of bed each day and forced those old bones to carry him around. Now, I have become him. I am old and need to tell this story before the creator takes me home. My great-grandfather lost his wife and first child at the Wounded Knee Massacre, shot down dead in the snow. His name was Gerald and his wife’s name was Tilde. They say when he heard the news of Tilde’s and Sarah’s deaths, he went blind in one eye—as if he couldn’t stand to see but half the world after that terrible winter day. When I was eighteen, my father was shot in the head. A hunting accident, they said—but death on Pine Ridge is never an accident. Mother said he was shot by history—that history holds a shotgun to all of our heads. I didn’t know what she meant at the time, but now, as I look back, it is clear. By age twenty I had hardened into a drinking, fighting young man. I was red with rage and living in that twenty-year-old body was like living in the center of a volcano. I lived with my mamma and two sisters in a beat up little cabin on the north edge of Pine Ridge Village. It was 1948. I would have been in the army except my father’s death relieved me of duty. My duty was to my mother—not that I was much good to her. She needed me to be the man of the family, but I was a hotheaded kid and had been since my father was shot. It was summer, near the fourth of July. There was going to be a big powwow and feast celebrating the returning vets, but my father’s death had even robbed me of that honor. I wanted out of there, one way or another. The night before the powwow two buddies and I started celebrating early with cheap whiskey, but the booze only stirred the volcano cooking in my middle. It was midmorning when I stumbled home still half-drunk and Mamma met me on the stoop. Just the sight of her standing there on that beat up porch in her bathrobe threw me over the edge. She’d been crying. “I need you Albert,” she said. “I need you to be a man now. Your father is gone, and I can’t do this alone.” Mamma spoke Lakota, so I grew up hearing English and Lakota mixed up in my head like word soup. She took a step toward me. “He isn’t coming back, Albert.” In almost two years she’d hardly spoken of my father. Why she chose that moment to start isn’t clear, but when she said I had to be the man now something in me broke loose. I held my breath trying to get my head to stop spinning. “Don’t Mamma,” I begged. “Albert.” She said my name like it meant something. It didn’t mean anything. I did not exist. “He’s dead, Albert. Your father is gone.” A fierce heat rose up in me, and I turned to her and said, “You think he’s gone? He is not gone. He can’t be. I’ll get him back, Mamma. I will.” I stomped past her and went into the cabin. She followed close behind, crying aloud now and murmuring my name. I grabbed a duffle bag and started stuffing it with whatever was near—a canteen, a can of beans, some stale crackers. I was a crazy man, not even clear what I was doing. My two sisters, Shawna and Sylvie, came out of the one bedroom still in their cotton nightgowns looking sleepy and disturbed. “Go back to bed.” I yelled at them. Mamma tried to hold my arm, but I gave it a rough shake. She backed up and took a place in front of my sisters as if afraid for them. There was fear in her eyes. I hated seeing that fear more than anything. I turned and ran out the door. I needed to get the hell out of there before I covered them all with this red rage that had taken my spirit. Mamma followed me outside. I dropped the duffle, went to the shed, and took down the saddle. I flung it over the back of poor George, our old, sway back horse. My hands shook as I tried to buckle it. I turned to my Mamma and said, “I’ll bring him back to you, Mamma. I swear.” Mamma screamed at me. “You can’t, Albert. Don’t you see? He’s dead, and you can’t reach him anymore.” “I damn well can. I’ll go to the ancestors and tell them to give me back my father.” I climbed on George’s back and rode off. When I looked back, Mamma was curled on the ground weeping and moaning, “Oh, my boy, my son, don’t go. Please don’t go.” I had only one goal as I charged off. I was going to bring my father back—or die trying. It was July—the sun at midmorning was already scorching, riding above me on its own race to hell. Within minutes I was sweating, my horse was sweating, the whole damn world was sweating. I wanted a cold beer—but in my twisted mind I thought the ancestors wouldn’t like it if I showed up with beer on my breath. Looking back now, I’d gone plumb crazy. My mind flickered with ugly images, all that I’d seen and done, all that had been done to us. It felt like history was a dark tunnel, and I was riding through that black tunnel, time flying by me. The images killed me again and again. I saw death, so much death. My younger brothers broken to bits in a car wreck, my dad with his brains splashed over the prairie, my uncle hanging by his neck in a shed, that same shed burning one night when I couldn’t stand to look at it any longer. Suddenly, I felt like it was raining down blood on me, a steady torrent of blood. It was getting in my eyes, blurring my vision, smelling of iron and rust and death. One eye went blind like my grandfather’s and then the other eye went blind, and I then I saw nothing but blackness. It scared the hell out of me. I hung on to the reins, clutching the leather as I raced forward in the dark, dark world. Old George must have sensed he had a blind, crazy man on his back. He slowed his pace, went to a trot and then, as if that horse knew what was about to happen, he sought the only shade for miles and miles. He clopped over to a small grove of trees and stopped. I slid out of the saddle and collapsed to the ground and passed out. Later, I figured out that I lay passed out beneath that grove for almost two full days. That was the beginning. I have spent the fifty plus years since putting together all that I learned while unconscious those two days. I suspect, on reading similar reports from other people that I died but was led back to life by those same ancestors I sought in such a mad frenzy. I was led back so I could tell this story to the best of my ability. They made me a Watcher during that time. And in seventy-two years, I’ve only met a few other Watchers. |